Barbie, or The Illusion of Choice

I ate a credit-card's worth of plastic this week and so did you

I have never bought my two daughters any Barbies. Does that mean we don’t own any Barbies? HAHAHA. No.

“When it comes to Barbies resistance is sort of futile,” the pop culture journalist Willa Paskin explained on the podcast The Daily last week.

“Like, I did not buy any Barbies and that was sort of intentional. And yet, there are, I think, over a dozen Barbies in our house now… Other people have purchased them and they’ve wandered into the house. I think the statistic is something like 90 percent of 3 to 10-year-old girls own a Barbie. And in America, 3 to 6-year-old girls, on average, they have 12 each.”

Paskin interviewed Greta Gerwig, the director of Barbie, the new blockbuster movie. It turns out she had had the same experience as Paskin and I:

The Barbies just …kind of…showed up.

“...her mother was not wild about Barbies for all of the feminist reasons we’ve already discussed. So most of them just sort of crept into the house, as Barbies have a tendency to do, as hand-me-downs.”

For me, it’s the resignation that stands out. That despite, “sort of,” good intentions, we have accepted the specific hell of this consumerist, late-capitalist moment.

Because it’s not just Barbie who apparently waltzes into your house like she has a mind of her own. Piles and piles of plastic and other semi-disposable crap that you do not want, like or agree with will creep in behind her. In fact, you (and it’s most likely you, MOM) must devote concerted unpaid time and effort on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis to getting rid of this encroaching wall of crap, lest it bury you alive.

And the plastic, it’s quite literally killing us.

Fossil fuel in a miniskirt

Compulsory consumption, especially of plastic, has dire consequences for our psyche, for our planet, and for our parenting. As Greenpeace points out:

According to a 2014 United Nations Environment Programme report, the toy industry uses more plastic in its actual products on a revenue basis than any other sector. Last year, American researchers quantified what each Barbie doll costs the climate. Every 182-gram Barbie causes about 660 grams of carbon emissions, including plastic production, manufacture and transport.

This is a useful reminder that plastic is just fossil fuel in disguise (99% of plastic is made from fossil fuels, like fracked gas and oil) and that it contributes to climate change throughout all its life cycle.

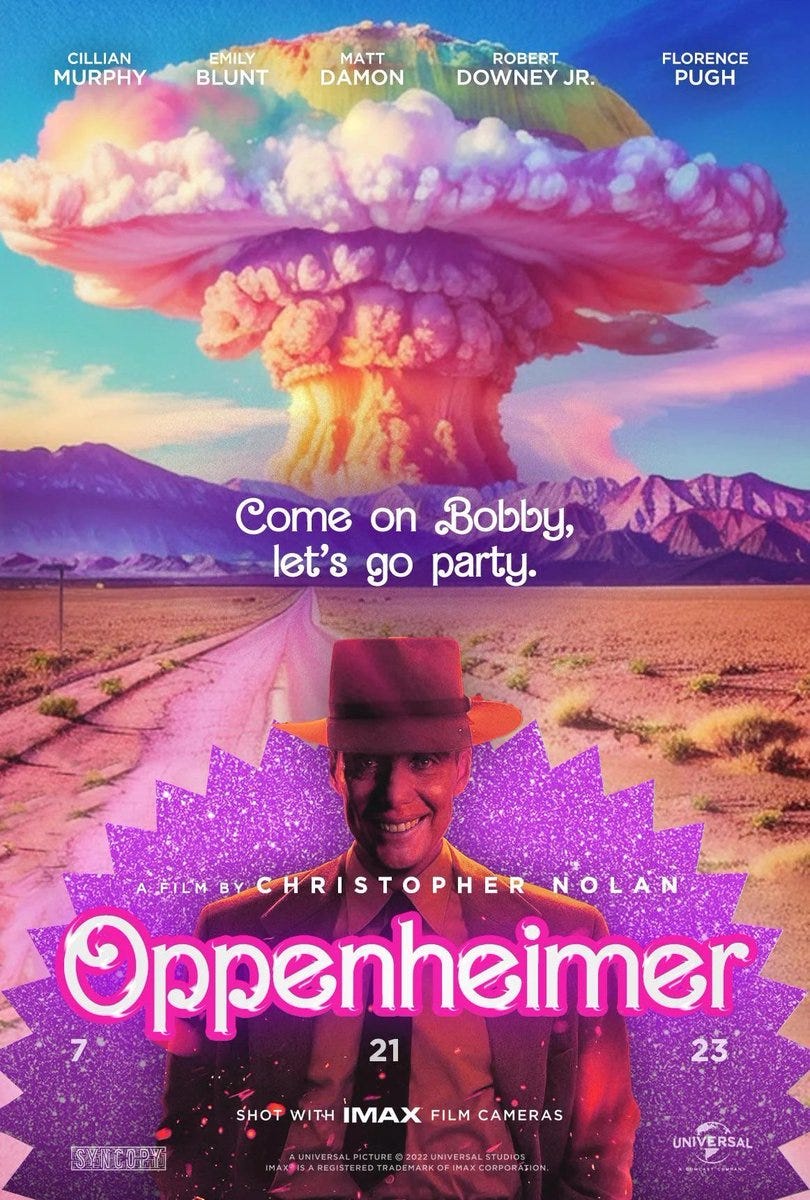

And as Tyler Austin Harper wrote in an astute piece for The Washington Post, the blockbuster double feature of Barbie and Oppenheimer reveals the villain origin story of the polycrisis.

The two movies actually have a fundamental, and disturbing, common ground. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the man behind our nuclear age, and Barbie — a toy that takes more than three cups of oil to produce before it lingers in landfills around the world — both tell the story of the dawn of our imperiled era.

In fact, experts are debating whether things like microplastics or radioactive isotopes could be the stratigraphic markers of a new epoch: the Anthropocene.

But there’s an important difference between them. Everybody is still afraid of the bomb; we have learned to stop worrying and love Barbie.

“ On one hand, we have the spectacular visibility and exceptionalness of the bomb — its mushroom cloud occupies the fuzzy boundary between the sublime and the satanic.

On the other, we have a climate crisis spurred in part by the everydayness of oil-saturated plastic products such as Barbie, goods so omnipresent in our lives that their harms are almost invisible to us — unlike the bomb, they produce delight rather than dread.”

I feel personally implicated by this dichotomy. Because I feel that delight.

I enjoy Barbie, at least in her current, self-aware movie incarnation, and I’m not alone, cause she’s selling a lot of tickets right now having it both ways.

As Paskin writes:

“Barbie” name-checks “rampant consumerism” as a sin and then makes every piece of plastic gleam so gorgeously that it feels as if the Pacific Garbage Patch might be worth it.”

Barbie is actually about that both-ways dilemma. It’s a smart, funny film about the contradictions of being a woman, the pressure to be all things to all people, including looking a certain way and acting a certain way and owning certain things.

Consumer spending is 70% of GDP. And women have control or influence over about 80% of consumer spending. Barbie was created to inspire generations of little girls to take their rightful place as leaders of the explosive growth of the consumer economy since the mid-20th century, which is inexorably connected to the rise of single-use plastics.

Barbie is, famously, not a baby doll. She is not a mommy doll, either. She’s a doll who shops.

Barbie is, famously, not a baby doll. She is not a mommy doll, either. She’s a doll who shops. (She bought her own Dream House in 1962, before she had any jobs).

That’s what little girls are being trained to emulate: a lifetime of fast fashion, cosmetics, beauty treatments, Target runs, Amazon Prime days, and endless shopping lists.

More Work for Mother

I stopped playing with Barbies around age 4, and I didn’t encourage my children to play with them.

But I’m still living my life, and particularly the aspects of my life most related to the sash I wear reading Cis Woman, on the same broad terms set forth by plastic-shilling corporations in 1959.

I still get suckered into getting new outfits for big occasions (even if I often rent them or buy used). I still conform to femme sensibilities of presentation in both professional and social settings, with all of the extra “pink tax” expenses and time that men don’t need to bother with. I still have a roll of plastic wrap and a box of gallon plastic Zip-locs in my kitchen drawer as backup for the beeswax wrap that just doesn’t work well for everything. I still sometimes go shopping! Just for fun!

And here’s the really tough one: I still, at some unspoken level, associate my children’s level of material turnout with my fitness as a mother.

I’m not quite sure how to unpick this snarl. On the one hand, the concept of the “carbon footprint” was famously invented by fossil fuel companies to make us think the crisis is our fault. And “conscious consumerism” is the lie that you are (I’m talking to you, MOM) going to personally mitigate an inherently untenable situation by spending even more of your time and effort shopping.

I’m against guilt-tripping myself or any other woman for her purchasing habits, for making the wrong choice in a world where choice is inherently an illusion.

On the other hand, I believe “we are what we repeatedly do,” that adopting daily habits more in line with my values reduces cognitive dissonance and steels me for the tougher collective actions that are needed.

Ok, so what if resistance weren’t futile? What would it look like?

Why you eat little pieces of Barbie

To get more perspective I called up my friend Madeleine MacGillivray. She’s a climate advocate and science communicator who focuses on microplastics, an ambassador for the antiplastic group 5Gyres and Climate Communications and Policy Coordinator for the group Seeding Sovereignty.

Madeleine told me that plastic is actually becoming even more important to the fossil fuel industry these days. As we move toward lower-carbon forms of energy and transportation, oil and fracked-gas companies have doubled down on plastics manufacturing. Their plan is to push more of their cheap plastic crap and packaging on the developing world.

She also explained that there’s an even closer connection between plastic pollution and the Barbie lifestyle: clothing.

“Thirty-five percent of microplastics in oceans are from synthetic textiles. About two-thirds of our clothes are made from plastic, and a lot of the fibers that shed from our clothes shed through laundry into wastewater.”

And get this: from municipal wastewater, microplastics make it into sludge that is subsequently sprayed on crops and persists into our food supply and into our bodies.

“There are little pieces of Barbie inside all of us,” she says.

Grossed out? Hang up your synthetic clothes to dry, don’t put them in the dryer, Madeleine says. That’s where a lot of the fiber shedding happens.

Madeleine prioritizes collective solutions. She lobbies for legislation to extend producer responsibility and reduce the use of single-waste plastics. For example, there’s currently a first-of-its-kind bill in NYC that would require restaurants to offer reusable takeout containers . (If you want to adopt this habit as a consumer, we use a company called DeliverZero in New York).

And she’s also a sometime model who loves fashion, and continuously reexamines her own shopping habits.

“I think we have to balance self-expression with not killing the planet,” she says. She channels her shopping impulses toward sites like the online designer resale shop TheRealReal. She looks for natural fibers, and for ways to remake things she already has. Overall, she advocates a gradual approach. “As someone who has adopted different shopping behaviors, I can tell you that in my own experience, power to people who can kind of go cold turkey; fast fashion to not buying anything,” she says. “I’ve definitely done the Marie Kondo thing and then regretted throwing stuff out.”

I’m feeling influenced. Madeleine is an influencer! Shopping is self-expression, and so is not shopping, shopping less, or shopping differently. I can enjoy Barbie as a symbol of femininity, imagination and joy, and abhor her role as an avatar of the plastic age. It’s important to cut back on my use of plastic not because it can single-handedly save the planet, but because my kids will do as I do, not as I say.

Maybe choice is an illusion, but the exercise of free will is what separates us from the wretched dolls of the earth.