Thirteen Augusts ago, in 2011, Hurricane Irene menaced Fire Island, the wisp of barrier island south of Long Island where my husband and I were on a ‘babymoon.’ The tide almost swallowed the beach. Everyone had to pack up and evacuate before the island’s ferry service was suspended. Volunteers knocked on doors letting us know the last ferry would leave Saturday at noon.

I’ll never forget how vulnerable I felt, pregnant and fleeing a potential storm. Irene blew over, but Sandy came to New York City just 14 months later, destroying the waterfront blocks from our apartment, keeping us inside with a young baby.

About two-thirds of Americans are ‘somewhat worried’ about climate change, while about one in ten say it’s a major factor in the anxiety—and another one in ten the depression—they are experiencing.

And these feelings tend to be more serious among women. A recent paper found that among 10,000 young people, the women were significantly more worried about climate change. They reported more negative emotions, more negative thoughts about the future, were more likely to say that "governments had failed," and expressed feelings of betrayal.

Researchers find, too, that it's not all in our heads: women around the world are physically, emotionally, and economically more vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

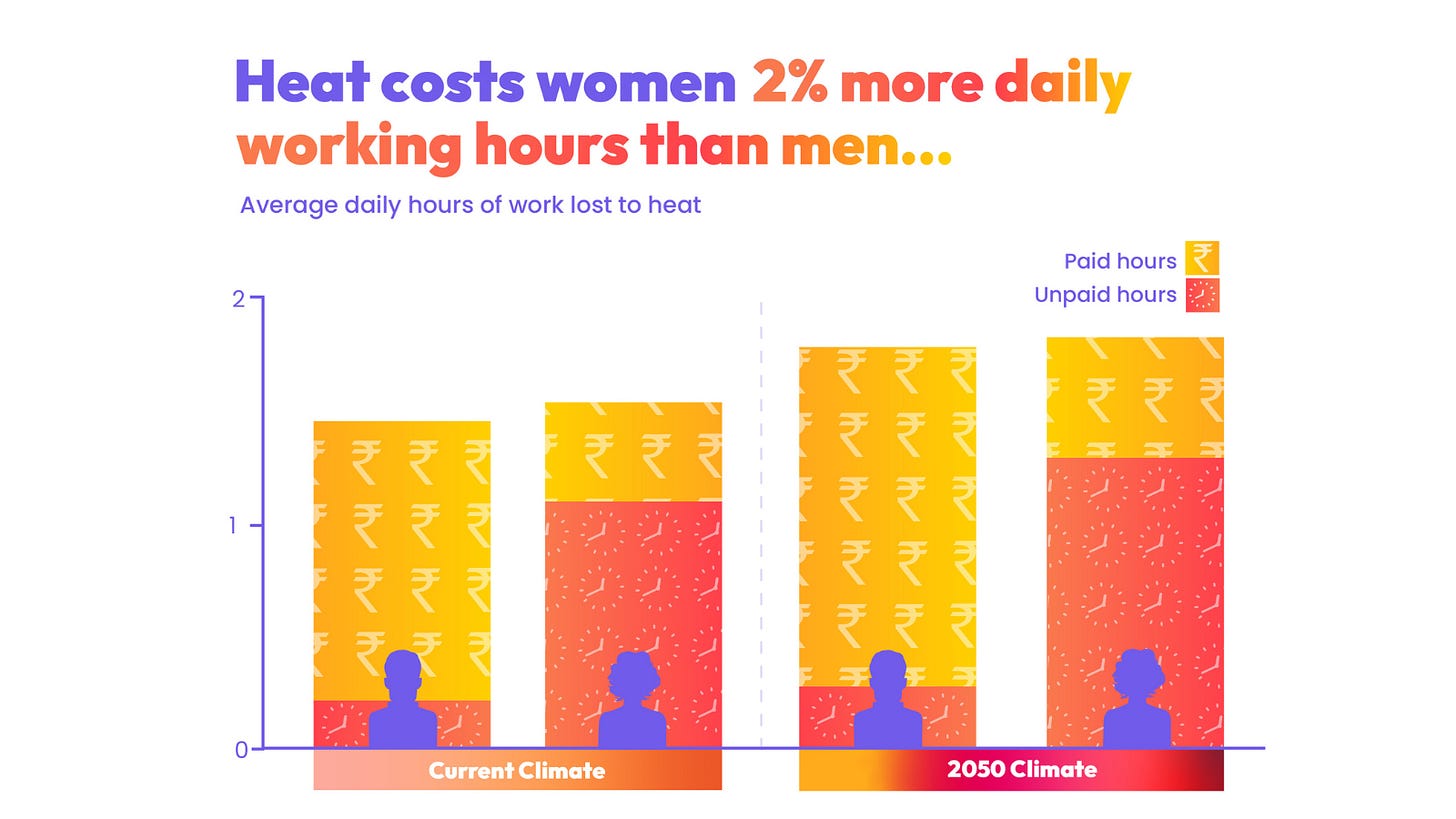

A recent report by the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center detailed how women in India, Nigeria and the United States experience a magnified gender divide from the effects of extreme heat.

The report focuses on women’s unequal burden of unpaid housework and care work, which accounts for an average 6 hours a day across the three countries studied (to men’s 1.2 hours). This household work is more difficult and dangerous, and goes more slowly in the heat, which robs women of time.

Women swelter in excruciatingly hot kitchens to cook family meals. In droughts, they walk farther to fetch water and firewood. When others in the family fall ill from heat-related illnesses, they care for them–-all of this at the cost of their ability to earn money, take care of themselves, or simply rest.

This description from the New York Times of a heat wave in Basra, Iraq sticks with me:

“Kadhim, [a laborer], returned home around 9 a.m. exhausted and eager to rest in his family’s air-conditioned living room. But as he cooled down, the women in his family began the hottest part of their day.

In the kitchen, his mother, Zainab, cooked a giant pot of chicken and rice for a religious holiday. The room had neither air-conditioning nor a fan, but she and her daughters-in-law still wore traditional long black dresses...

The gas flame and the steam from the pot turned the kitchen into a sauna. Zainab cooked in extremely dangerous temperatures — a heat index above 125 degrees — for more than an hour. Her risk of heat stroke was severe. But Zainab felt obliged to keep cooking for the festival.

Heat harms maternal and neonatal health. It’s linked to lower birth weights, pre-term births, stillbirths, gestational diabetes, dehydration and endocrine dysfunction, and placental abruption.

And as I experienced, the perinatal period is often a time of onset of eco-anxiety; the pregnant body and developing fetus are especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change, and becoming responsible for a life that will likely continue decades into the future brings its own flavor of climate anxiety.

This is before we consider how the economic and social disruptions of climate change are visited unequally on the bodies of women and other marginalized people. For example, child marriage rises in the wake of drought–-more than doubling in Ethiopia in the space of one year, Unicef reported in 2022.

Empowering women and girls is essential to climate action

There is a flip side to this story. Empowering women and girls turns out to be essential to climate action, for a host of different reasons.

As I wrote last year for NPR:

The most direct reason is that when girls are allowed to stay in school, they tend to wait longer to get married. …

The nexus between fertility and climate can be a tricky issue to talk about ethically. … coercive reproductive policies have no place in a climate agenda that respects human rights.

Still, Drawdown, a nonprofit which focuses on solutions to the climate crisis, calculates that investment in voluntary – key word – family planning programs, together with universal high-quality education, could reduce global emissions of greenhouse gases by 68.90 gigatons between 2020 and 2050.

The other reasons that gender justice is key to the climate crisis are more subtle and maybe more interesting. They have to do with the particular experiences of people who are born, socialized as, and/or identify as women, the kinds of policies they tend to support, and the kinds of leadership they inhabit.

It’s about everything from teaching girls to swim in Bangladesh so they don’t drown in floods, to electing women, who are more likely to vote for climate protections.

For example, there’s an organization, CAMFED, that I’ve written about twice now. They pay the school fees and expenses of girls in Ghana, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. They then hire their graduates to be “climate guides,” training other women in climate-smart agriculture techniques, like a cheap form of drip irrigation done by pricking holes in reused plastic bottles.

Esnath Divasoni was educated with the help of CAMFED and now works with the program in Zimbabwe. “In communities where women are actually educated, they are at less risk of being affected by weather-related extremes,” she told me, citing research. “When one is educated, you are more able to make decisions on your own. You have more critical thinking skills.” And the hope is that when women make those decisions, they will be informed by their care and concern for others.

My climate consciousness grew as I grew into motherhood, until in 2022 I quit my full time job in journalism to work and write at the intersection of climate justice and children’s well-being. Nothing has been better for my eco-anxiety than diving into joyful, purposeful action. I’ve come to see my climate emotion as a gift that reminds me of how connected I am to each other and the fate of all living things. That may not be an essentially or universally female experience, but it’s essential to my experience as a woman and a mother.

Some links; Good news

An Indigenous-led campaign has emerged victorious in Ecuador: “a historic referendum to halt the development of all new oilwells in the Yasuní national park in the Amazon, one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet” “which is also home to the Tagaeri and Taromenane people, two of the world’s last “uncontacted” Indigenous communities, living in voluntary isolation.” I’ve been supporting one of the backing organizations for awhile: Amazon Frontlines.

Wow! it was beyond amazing to be part of this conversation with a teenage journalist about climate emotions: "One of the most encouraging points that Kamenetz made during our talk was that I’m not alone. “

Heat Is Not A Metaphor - Alexis Pauline Gumbs on heat, whales and menopause (just read it, I promise)

Very excited to read Emily Raboteau’s next book, beautiful cover.

I loved How To Blow Up A Pipeline, and interviewed the star/writer; enjoyed this critical consideration of this and other women-centered ecothrillers, with lots of ideas of what to watch next. Related: Foe, my next read (and a forthcoming movie)

Amy Westervelt – incisive reporting as ever– Big Auto and Big Oil used to be best buddies in the climate-denying business, but now Big Auto sees a path forward with electric cars and Big Oil is attacking them.