Hello friends.

Happy Mothers’ Day.

I got a note from a reader last week telling me how both she and her kids are going through it. Learning about environmental disasters in school, with no place to put those feelings. Triggered by unseasonable weather. Her ten-year-old saying sadly at dinner that the world will be broken by the time she grows up.

Then I saw this passing comment by

:“One thing that I do tell women vacillating about motherhood is that these kids know their future will be radically shaped by environmental catastrophe. Even if you say little to nothing about this, they will find out (by around age seven) and when they ask you about it — "Is it true...?" — you will not know what to say because the truth is too uncertain and awful and you are trying to give them a safe feeling inside.”

I felt the call!

Yes, the truth is uncertain and also awful. But there ARE things we can say. And we must say them.

There is one statistic more than any other that started me on the road to writing this newsletter. I found it in 2019 when I commissioned a survey of parents while working at NPR, and almost the exact same numbers turned up in 2022 when we asked the same question with the Aspen Institute.

Four out of five parents say children need to know about climate change.

Just under half have talked to their children about it.

I understand why we don’t. We don’t know what to say. We are upset ourselves. We want to make them feel safe, and the truth is scary.

But that silence has costs.

75% of youth worldwide say the future is frightening. More than 45% say climate-related feelings negatively affect their daily life and functioning.

I read this somewhere, but I can’t find the source: we cannot protect our children from the truth of the climate crisis, or any terrible reality in the world for that matter. We can only protect them from being alone with the truth.

So for this Mother’s Day I want to give you a quick guide for talking about these realities with children you care about, whether you are a parent, grandparent, teacher, or caregiver. I have been working on refining these points through many conversations, presentations, and writing over the last few years.

I believe this guide applies equally well not only to environmental crisis but to the other components of the polycrisis —the big, overwhelming, existential risks humanity is facing.

First, put on your own oxygen mask.

Then, learn more about these feelings.

The next step is to listen and talk to your kids.

Finally, take action together.

Step 1: Secure your own oxygen mask

My friends Elizabeth Bechard and Jennifer Silverstein published a paper in 2023 reviewing the literature on how climate concern affects parents’ mental health. They found that in relation to the climate crisis:

Parents experience emotional distress that can be described as moral injury. This means we feel responsible for the harm that comes or may come to our kids because of our part in causing this crisis. This increases our anguish.

Many parents use distancing strategies to cope. We tend to be more climate-concerned than non-parents, but we expend energy trying not to think about something that is actually very much on our minds. This is not a recipe for emotional health.

But, here’s the good news. For some parents, embracing the challenges of climate change can be a catalyst for personal growth, meaning and even hope.

It certainly has been that for me.

If we’re going to successfully parent through global crisis, our kids can’t be the only people we talk to about it. We need support. And that support often comes most readily by breaking the silence and talking to other parents about this. Odds are that people around you are feeling it too, even though it can be taboo to discuss.

Jo DelAmor, who I’ve interviewed here, runs online Work That Reconnects programs for parents.

Step 2: Learn About Climate Feelings

The term “climate anxiety” has gotten too popular. It’s limited and not entirely accurate. Anxiety disorder can be a clinical diagnosis. But climate emotions are not pathological. They are normal and common. Grief at experiencing a loss is normal and adaptive. Fear of extreme weather is normal and adaptive. Rage at the fossil fuel companies responsible for climate harms is normal and adaptive.

Lisa Damour, the clinical psychologist and author, says, “Mental health is not about feeling good or calm or relaxed…it’s about having feelings that fit the circumstances you’re in and then managing those feelings well, even if those feelings are negative or unpleasant.”

Our kids’ bad feelings are not the problem to fix. Climate change, fascism, inequality are the problems. And we get closer to meeting the problems with sufficient energy, the more of us are in touch with the truth.

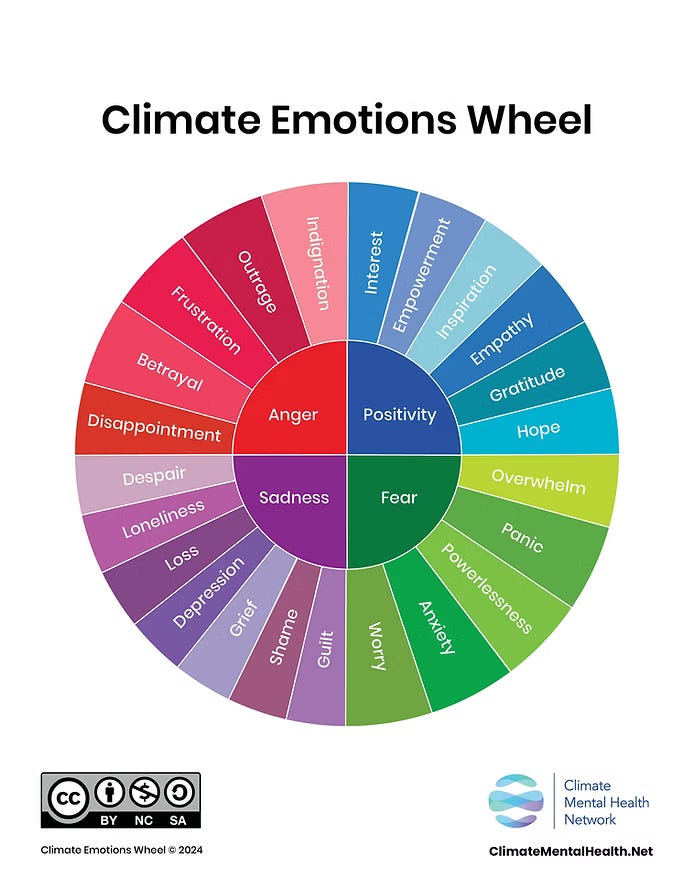

In 2023, I approached Panu Pihkala about creating a “climate emotions wheel” based on his 2022 paper.

The wheel depicts the positive along with the negative. It can be the basis for a conversation with your kid about climate feelings, or you can use art supplies to draw your own climate emotions wheels together.

As the wheel shows, it’s important to realize that polycrisis emotions are not all negative. When you allow yourself to get in touch with the bad ones, it opens you up to experience the good ones.

More recently, we’ve put out resources on climate grief, with lots of models and information on how people can process difficult emotions. Here is a simplified image of that process. The resources include a guide with ideas of activities to try with kids.

Step 3: Talk and listen

“Have you thought about climate change?”

“What do you know about climate change?”

“What do you think about when you hear ‘climate change’?”

“What questions do you have?”

“What do you know about the solutions people are working on?”

“What do you know about how people are protecting nature and the soil?”

”What do you know about clean energy and transportation?”

”What do you know about waste?”

“Good question–let’s look it up together.”

“Tell me more about that.”

“What have you noticed about the air quality/the heat/the floods/lack of snow lately?”

“Do you have any questions about that?”

“How are you feeling about all this?”

“Can we draw how we are feeling? Can we play how we are feeling? Can we pick a song that sounds like we are feeling?”

“I feel the same way sometimes.”

“I get why you’re mad/sad/scared.”

“Thanks for sharing that with me.”

“Lots of people feel that way.”

“Don’t worry about that.”

“Everything will be fine.”

“Don’t get so upset.”

“I hate seeing you upset.”

And here are the things I say to my kids the most:

I get why you’re worried. It’s ok to be worried. I am worried too. But there are three things to keep in mind.

One is that no one knows exactly what is going to happen. No one can 100% predict the future. Our brains are wired to pay more attention to the scary scenarios and the bad stuff—and that can be helpful. That is our brains trying to keep us safe. But we also need to try to pay attention to the good stuff. Humans have gotten out of some pretty bad spots before. This is a unique and exciting time to be alive, when the world is changing fast and people have to work as hard as we can to make a better future.

Two is that we are not the only ones who know this is a problem! Millions of people all around the world are working hard to fix it—scientists, engineers, electricians, community builders, leaders, activists, storytellers. It’s not all up to us.

Three is that it’s ok to take breaks from thinking about all this sometimes. We can always come back when we are ready.

And of course, of course, I will always love you the most and do everything I can to keep you safe.

Step 4: Take Action

Taking care of the next generation, helping raise committed, heartful, ethical humans, is itself an essential form of activism.

In the early years, climate response overlaps with skills and behaviors that we all want our children to experience, such as

Care of self and environment—don’t waste food or water! Recycle and compost!

Health and safety (like drinking water, wearing sunscreen, wearing a mask if the air quality is bad)

Nature & outdoor play

Empathy for all living things

Emotional regulation

Awe and wonder

Efficacy and agency

Older elementary school students are ready to engage in outward action. This is the prime time, when they still are interested in doing what parents are doing.

“Let’s find out a group that is working on this problem. Let’s throw them a bake sale. Let’s write them an email. Let’s call the governor/the mayor. Let’s go to a rally. Let’s draw a picture of the solution. Let’s do something to help the animals and plants around us. Let’s prepare our house for rough weather…”

As children get older, action, and emotions conversations of course, get more challenging. This aligns with the developmental tasks of adolescence, such as independence, rising concern with fairness and justice, as well as more sophisticated emotional regulation and social-emotional literacy.

Teens’ climate/polycrisis emotions can be messy because teens’ emotions in general are messy. They won’t always be so eager to take your suggestions. They are seeing hypocrisy everywhere and they are pissed. They may be angry at you, as well as politicians and fossil fuel CEOs. They may assume a veil of indifference.

This is fine.

Model the behavior, like activism, that you want to see without insisting they take part. They deserve to know that we, the grownups, have got this.

Ensure they have access to good information. Including about solutions.

Lean in and celebrate the things that give them joy and calm. Help them build up their tools for emotional regulation.

Offer them opportunities to be with peers, working on the problems they express concern about. (You can only lead them to water here—can’t make them drink).

Draw them out and listen to their opinions and questions. Be a safe space to come back to.

Step 5: Repeat

Like the conversations about bodies, sex and consent; drugs and alcohol; screens; bullying; the conversation about existential threats is hardly a one-and-done! The path you are walking is one where you’re more honest with your kids, and you both have more ways to acknowledge and manage tough emotions.

This is a path to a better world.

Some links

I got to write for National Geographic about one of my favorite topics, post-traumatic growth.

Loved

‘s recent post (dovetails with this topic!) on “Anything Mentionable Is Manageable.” Preorder her book!https://substack.com/home/post/p-163057977

So helpful, thank you! I often feel frustrated that books and media for kids suggest the same things to help the planet/climate that I did as a kid 40 years ago. Not that recycling and using less water aren’t important but I sometimes feel like, we’ve been doing this for years and things are probably worse now! So I appreciate your ideas and questions to ask.

Thank you for making this accessible to unpaid subscribers. This is too important not to share widely. I just had a big conversation with my 18 yo this morning about the climate crisis, spurred by the threat of nuclear war between India and Pakistan in the news. We went on to talk about what it's been like to grow up with global warming as a threat since he was old enough to begin to grasp it. We talked about how he understood it from the conversations in his classroom, led by the teacher, that they had to do their part, which is a good message. But at age seven, being appropriately ego-centric, he believed it was up to him to solve it single-handedly. He was reflecting today that the teacher never addressed that feeling, but he was sure all his classmates felt the same way. So YES, I agree we need to get better at having these conversations with kids so they can understand their feelings are normal, appropriate, and can be used to do good things that will contribute to helping with these issues, but likely not solve them. And that no one knows what is going to happen exactly and the most important thing is working TOGETHER.