The Power Of Community For Parenting Through Crisis

"We're all feeling this. Everyone has some cry of grief stuck in their throat, or some achy heart, and it's just starting to feel harder and harder to act like that's not the case."

How are you? How is your heart?

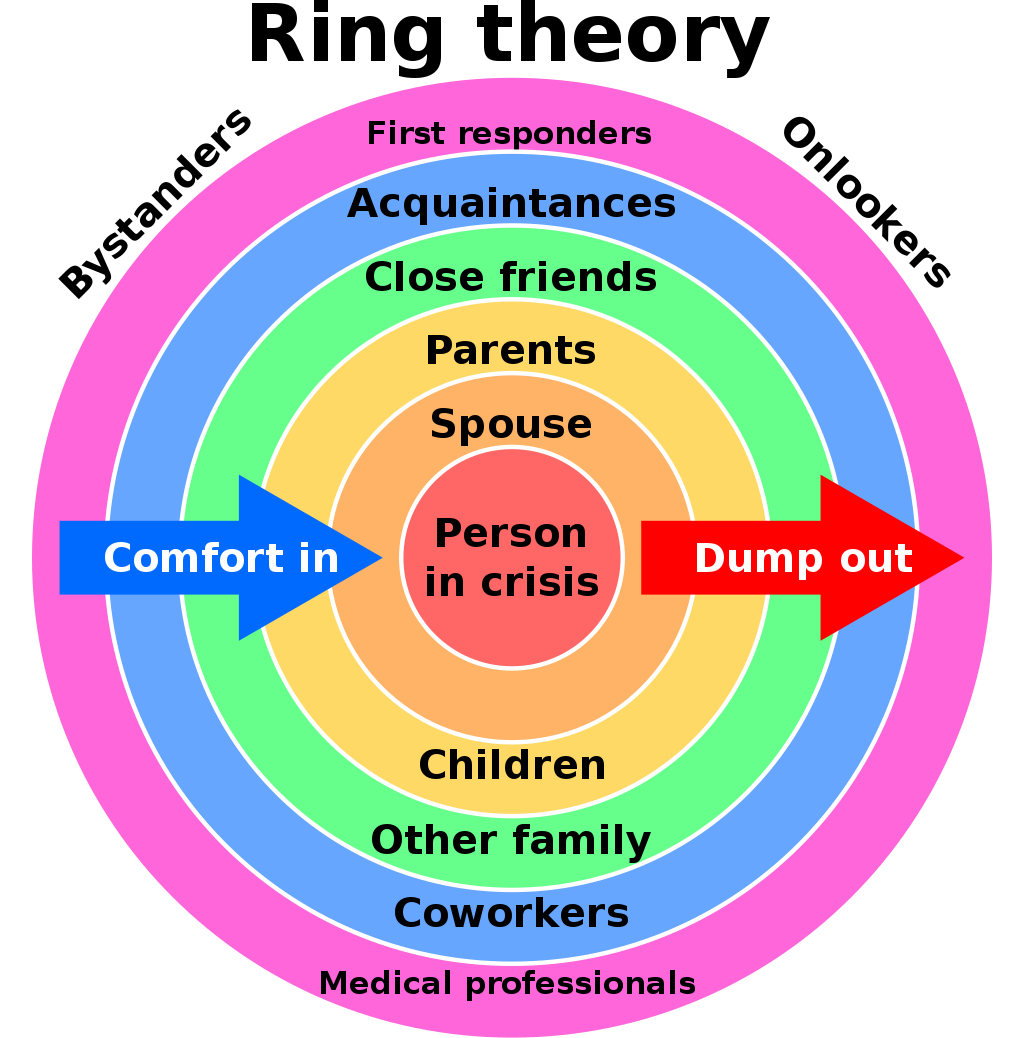

In my conversations with friends, colleagues and acquaintances this week of terrifying bombardment, siege, and mourning, I’ve often heard or invoked a version of Ring Theory. This is the idea, from clinical psychologist Susan Silk, that when there is a crisis, one should observe the “kvetching order”; direct only comfort inward, towards people who are more directly affected than you, and dump your stress outward, toward people who are less directly affected.

The war and humanitarian crisis in Gaza has many, many intersecting rings, and overlapping ripples out, but I’m doing my best to kvetch towards those less affected, and absorb the pain of those who are more affected. That’s my practice right now.

What else? You can call for a ceasefire. You can also give money, although the status of aid getting through is unclear as of this writing. I’ll be donating my next two $50 subscription fees for this newsletter to Doctors Without Borders.

No matter where you are in the kvetching order, talking almost always helps. One of the things I’ve been privileged to do this week is interview parents about how they are approaching conversations with their kids about the war, for a forthcoming story. And I want to share some wisdom from my friend Kavitha Rajagopalan, an Indian-American writer who is showing her children statements from Israeli peace activists, and letting them know:

“Compassion and empathy and clear-eyed assessment of atrocities does not require us to turn against any particular group, or take a side. We can see suffering. We can call it out. We can demand better from our leaders.”

Sounding the same note, this video was shared on Facebook by my friend Jay Michaelson, whose Substack you should read. This is a 19 year old Israeli from Kibbutz Be’eri, which was the site of a horrific massacre by Hamas fighters. The whole thing is worth watching, and reading the translation; she speaks with empathy both for the victims in her own community and currently in Gaza.

“HOW AM I SUPPOSED TO WAKE UP EVERY MORNING AND KNOW THAT FOUR-AND-A-HALF KILOMETERS FROM ME, FROM MY HOME IN KIBBUTZ BE’ERI, IN GAZA, THERE ARE PEOPLE FOR WHOM THIS IS NOT OVER?!

…I know what I want. I want a just peace.”

This young person is in the center of a white-hot ring of tragedy, and she is speaking up to demand that her pain not be visited on others. It’s powerful.

Finding community to work through our pain

This week I bring you the highlights of a recent interview with Kristan Childs and Teddy Kellam. As part of the Good Grief Network, they have collectively spent hundreds of hours with parents doing emotional processing around climate change. They run both 10-week support groups and shorter workshops for parents who want to express these feelings so they can become “unfrozen” and “unstuck,” be there for their kids, and take meaningful action together.

I actually met Kristan and her family years ago in Washington DC when I was reporting for NPR. Her husband Park Guthrie founded the Schools for Climate Action campaign in the wake of the Tubbs Fire in Sonoma County in 2017. But Kristan was growing increasingly anxious about climate change, especially about burdening her kids with the responsibility to ‘fix’ it.

“Park and I did a Good Grief 10 week program together, and it was so deeply transformative for both of us,” she said. “He got to the absolute tenderness and sorrow underneath his outrage. And I realized, one of the things that was making it really hard for me to talk to the kids about the climate crisis was because I had so much of my own feelings about it.”

Here’s their top pieces of advice on how to approach this work and the conversation about climate change with our kids.

On not avoiding the conversation

KRISTAN: Climate change is here. Kids are hearing about it. Kids often know more than the parents think they know. Jo McAndrews is a British psychotherapist who deals a lot with talking with kids about climate change, and she says:

We cannot protect them from the truth of this. We can only protect them from being alone with it.

How the climate talk is like the sex talk

We definitely are not advocating dumping a lot on the kids. It's like sex talks. You know, you kinda check out how much they've heard, what they're wondering about.

Listen, don’t fix

Just listening is so huge, especially as they get older, just listening really warmly and interested, and not trying to make them feel better. If they're really grappling with something. If you try to fix it or make their bad feeling go away, you're kind of saying to them like, Whoa, I can't handle your big feelings. And then we just offer some general questions like, What have you heard? What do you wish you knew more about?And how are you feeling about what you've heard?

And then, empathy like, oh, it's gotta be really hard to be living with those questions. I'm so glad you brought this up. I feel sad about that, too.

Why parents need to do their own inner work

Being able to be calm even in the face of this hard stuff, is so grounding to kids. If you have all this agitation and panic around climate change, they can pick up on that. I mean, we're all just a bunch of nervous systems sponging off each other, particularly kids with their parents.

Getting out of survival mode

TEDDY: To me it goes back to the bigger culture and how we deal with emotions in general, and how we want to click them off, and we have our attention grabbed by these little devices. And our attention is a very precious resource, and it's really hard to keep our attention on something that's very uncomfortable.

The nervous system, when it's in heavy emotion, is, you know, either up here in the sympathetic, in the fight/ flight, or down here, in the freeze and the numbing out. And we can't really get to meaningful action. And we can't really be there for our kids if we are weighed down with these heavy emotions that we're not letting move through us. You know, we're just kind of in survival mode.

So part of this movement, part of what Good Grief is asking, is that we actually let some of those heavier feelings—we use the umbrella term eco-distress—come to the surface and we express them. We express them vulnerably if we can.

How to feel your feelings

We do journaling. We do embodiment exercises to help settle the nervous systems in our parenting groups. We offer ones that they could also use with their children.

An exercise they use in their workshops is called 5-4-3-2-1—an invitation to tune into your senses.

We do guided practices where we actually spend time sitting with the hard feelings and talking about being with them. So like maybe 5 to 10 minutes of guided practices, and then the core of the meeting is sharing.

The really magical piece is in community. And so that can actually shift things. And the undoing of aloneness is really critical.

Good links

Kristan and Teddy work with the Good Grief Network, which offers 10-step programs, workshops, a journaling program, book clubs, a program for teens (GGNZ), facilitation training, training for organizations, lots of events, and tons of resources.

There’s a UK-based Climate Circle for Parents/Carers/Guardians on October 25.

Tips for talking to kids about violence in the news

Classroom resources for processing the violence in Israel and Gaza

My new column, on climate and early childhood: Little kids need outdoor play — but not when it’s 110 degrees

Turning over this quote in my head: “In today’s world, whatever happens on the battlefield can be overturned in the information realm, so the battle of the story matters as much as the battle on the ground,” said John Arquilla, a retired professor of strategy at the Naval Postgraduate School.

I’ve also been ruminating on this, and sharing it with others: some contrarian thinking on the idea of “taking a stand”, from Bayo Akomolafe:

the language of ‘stands’ begins to feel less secure, less monumental, more slippery, slushier, and beyond human. In a sense, we are diagonal beings. Or rather, we are diagonal becomings. Have you ever tried standing perfectly still? If you do, you might notice you are actually moving in barely perceptible ways, leaning back and forth, vibing in the minor key. Yes, it would seem 'standing' is always troubled by the quantum inclinations that ripple through our claims to stable and resolute positionality. The rectilinearity assumed in the mathematical precision of a stand hides from us the ways we might be participating in and sustaining the very conditions we would like to rectify. The ways we are already moved.