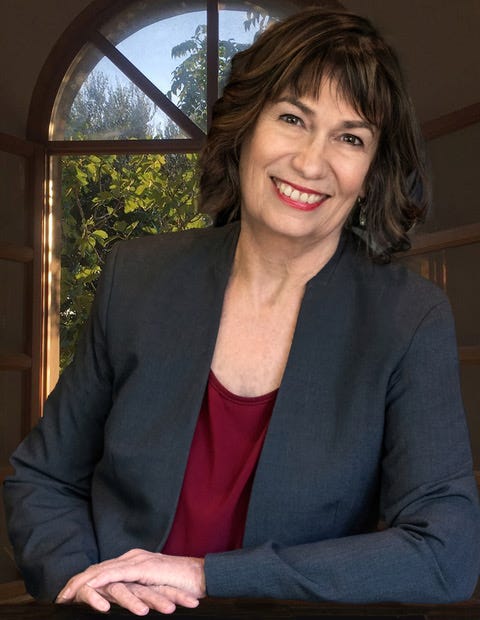

Leslie Davenport is truly one of the best, wisest specialists in climate distress, resiliency, and planetary health that I know. She leads the Climate Psychology Certification Training at the California Institute of Integral Studies. I was lucky enough to collaborate with her and get her input on the parents resources I worked on with the Climate Mental Health Network, on talking to kids about climate emotions.

Davenport wrote a lovely climate emotions guide for tweens, called All The Feelings Under The Sun, and she’s now out with a new book from the American Psychological Association’s Magination Press, titled What To Do When Climate Change Scares You. It’s a practical, empathetic workbook for kids 6-12. Part of what’s important about it is that it elevates the visibility of climate concern. It’s part of a series that includes titles for kids who struggle with separation anxiety and perfectionism, and that are intended for use by children’s therapists, in school counselor’s offices, and in libraries.

“They’ve tried to have their finger on the pulse of issues coming up for kids,” Davenport says of the APA.

We had a great conversation about helping kids and adults cope, and how climate change challenges and expands our concept of mental health—a big preoccupation of mine recently.

What’s inside this book? Is it cognitive behavioral therapy?

There’s certainly CBT exercises included, but there are a variety of approaches. For example, there’s nature art, which comes more from eco-psychology and expressive arts therapy.

With any form of climate-oriented mental health, there’s some things that make it unique to climate and other things that, whatever the triggers for distress may be, the tools are often the same.

And tell me more about the purpose of these exercises and worksheets?

It’s practical – it encourages kids to explore their own thoughts and feelings and learn how to work with them using a range of emotional intelligence skills. They are also encouraged to become changemakers and find a role to play in creating a safer, healthier, more just world. It’s self-guided. Kids are invited to focus on the things that matter most to them: what’s happening in their home, school, and community; what they are most worried or curious about. And then it provides support and direction so that they can get what they need.

I’m curious about how you think about what makes climate psychology or climate mental health distinct from general mental health. And how should we treat climate anxiety differently from general anxiety?

Most of the time, whether kids or adults, when someone comes to therapy, the issues are somewhat resolvable. Should I take this job? Should I move? Can I communicate better in this relationship? Often there’s an arc to therapy: there’s a problem, here’s some ways to work with it, it moves toward a resolution.

With climate change we know that we are on an escalating trajectory related to impacts, with emotional distress rising in tandem. So it’s less about resolving [issues] and more about becoming skillful with the feelings that get triggered and learning tools to lower the intensity of the distress. It has more of an ongoing awareness with ebbs and flows of feelings and building confidence and competence in facing life’s challenges.

And how do these feelings show up differently with kids? We know that climate anxiety is showing up as more acute in young people.

It varies considerably with different ages. Young kids, roughly up to the age of 6, are generally not practiced at putting their emotions into words and making sense of what’s happening. So sometimes it shows up as acting out, stomachaches, headaches.

If children live in an area that is experiencing direct climate impacts, such as evacuation from flood or fire, it can create a breach in feeling safe and secure and building attachments. This may come out as regressive behavior that seeks lots of comfort and reassurances.

This book is for the 6 – 12 age range, when they often start to learn about climate change, but may not have all the facts straight. There’s a story in the book about Emma, a girl who overheard a news story of coastal sea rise damaging homes. She didn’t understand that they lived in a different town and she was afraid to go to sleep for fear of her bedroom flooding. This may sound extreme, but kids overhear all kinds of things and if it’s not talked about, they often harbor very inaccurate beliefs. The book goes into supporting Emma to not only learn more accurately about climate change and her own community, but also includes a look into the restoration efforts her family and community are involved in. The book then brings the reader back to their own questions and concerns – what they want to learn more about.

As kids get even older, they naturally orient toward their futures – do they want to go to college, pursue a profession, imagine themselves with a family of their own one day?

For many, their future feels hijacked by climate change and the level of distress is very high with teens and young adults.

Do you envision this book as a tool for teachers? Because I hear a lot from teachers that they need ways to help kids handle the feelings that come up when talking about climate change.

Yes, the exercises are very adaptable to classrooms. My book for tweens, All the Feelings Under the Sun, is often incorporated into curriculum, and this one for younger kids is structured very similarly

.

When kids are learning about climate, they’re processing both information and emotions. I recommend an approach called “toggling.” This involves following up difficult information with approaches that support the feelings that get triggered before they go back into learning more. This could be as simple as naming a feeling they have, perhaps using a tool like the Climate Emotions Wheel, or doing a drawing, or mindfulness breath practice together.

I’m interested that you included ways of taking action on climate change, because this probably isn’t the case that if a child is having trouble falling asleep, for example, that you would have them, say, call 311 and lodge a nighttime noise complaint with the city—addressing the root of the problem in that external way.

In addressing climate change we need two fully robust parts: 1. Internal tools: self- regulation, breathing practices, calming tools that we’ve been discussing. And 2. External tools: finding ways to be part of the needed and necessary change and joining with others doing the same.

Over time, discernment develops. It the example you gave, it may make more sense to do a breath practice to help fall asleep, but consider lodging a complaint the next day. There’s not a simple formula given the complexity of climate change, but if the internal and external tools are strong, there can be creative solutions as situations arise.

When I work with youth activists who are teens through early 30s, they often have a hard time at first practicing self-care. They feel that the urgency of the situation makes that self-care indulgent. The truth is, without that balance, there are very high levels of burnout and overwhelm. We need to replenish ourselves to be changemakers over the long run.

Sometimes I get people on the other end of the spectrum: “Just make me feel better so I can forget about climate stress.” I have to help them see that everyone has a role to play because, until the system shifts, these feelings are going to continue to be triggered. We need to feel more empowered and that we can all make a difference.

In training in the mental health field in climate psychology, we are challenging how it’s been done before. There’s been a big emphasis on the mental health profession being neutral and following what the client needs and wants. But there’s a challenge to the ethics of that now in a good and needed way.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Golden Hour: climate, children, mental health to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.