My kids don’t like my chocolate chip cookies. I like to load them up with as much chocolate as physically possible. They prefer a more normal, predictable, balanced ratio of chocolate to cookie.

They are clearly wrong, but that’s not my point. My point is that I recently had a chapter published in the open-access Handbook of Children and Screens—free to download—titled “Education Technology During the Pandemic and Future Emergencies.”

I am the least educated and the lowliest-affiliated of a long list of brilliant co-authors: Justin Reich (MIT), Cristóbal Cobo (World Bank), Sarah Dryden-Peterson (Harvard Graduate School of Education) , Eric Klopfer (MIT), and Torrey Trust (UMass Amherst).

The chapter explores what lessons we can apply from the massive disruptions of COVID-19, to emerging polycrisis conditions: extreme weather, conflict, violence, migration crises and more pandemics.

Our institutions, such as schools, were not built for this.

“Our school systems were built in an age of climatological stability, and they will now be operated during an era of rapid changes to sea levels, climate, and weather patterns and resulting displacement and migration….What we once called “interruptions” in schooling will become the ongoing conditions under which schools must operate.”

Interruptions become ongoing conditions.

In other words, what we once experienced as the chips, will more and more become the cookie. And we need our cookie not to crumble.

This piece germinated in the very early days of the pandemic, when schools shut down worldwide. I had reported from New Orleans two weeks after Katrina and for many years afterwards. So I knew that when kids stop out of school, when their worlds turn upside down, even briefly, it can derail their lives.

I connected with Justin because he knew all about the limitations and inequities of online learning, and Sarah, who was an expert in “education in emergencies,” and produced a piece on the likely outcomes of school shutdowns, most of which came to pass.

Education in emergencies is the term for something very good in the midst of something very bad.

Traditionally in a war or a refugee crisis, humanitarians didn’t think much about education or childcare for the victims. These took a back seat to safety, food, medical care. Understandably so.

These days, however, we have a massive boom in child refugees. Which, of course, is only likely to get worse.

“Between 2010 and 2023, the global number of children displaced due to conflict and violence more than doubled from around 18.8 million to the current number of 47.2 million.

According to UNHCR, over 2 million children were born as refugees from 2018 to 2023.”

In 2022 alone, 12 million children were displaced by extreme weather events.

We also have mobile phones, which can help deliver learning. We also have a greater scientific understanding of the long-term impact of childhood trauma and toxic stress, which care and education programs can mitigate by offering support, meaning and hope in the midst of crisis.

So there is both increasing means and increasing motivation to provide learning and care in some form to children who are sleeping under tarps in various places around the world. Hence, the field of “education in emergencies.” I find this exciting. It’s a moral innovation, and a huge challenge.

I’ve reported on “education in emergencies” efforts with displaced Ukrainian children, Syrian refugees in Lebanon, and years ago among migrant workers’ children in Mexico.

It’s unpleasant to say so, but Americans tend not to care very much, or very steadily, about these children. In fact, the MAGA faction has voted to keep international refugees out, and to create a new displaced-children crisis within and across our borders through mass deportation.

Nevertheless, I think you, my readers, care about these kids. And it’s not only heartless not to, it’s stupid not to. Because of demographics, the children of the Global South are literally our future. More and more of the working-age adult population in the 2050s and beyond are coming from those over-there places.

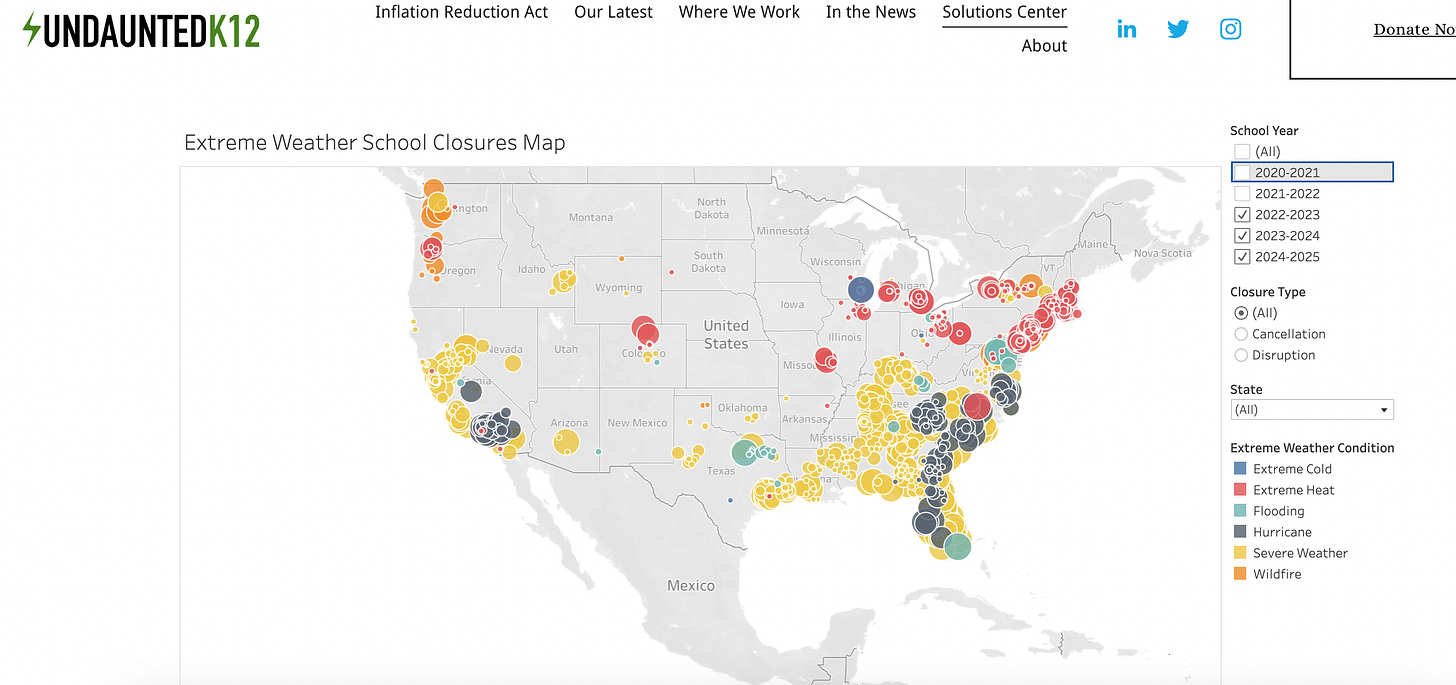

It’s also the case that these disruptions are coming home to us. This map from Undaunted K12, a school decarbonization group, shows school closures due to extreme weather across most population centers in the United States in just the past few years.

So what is to be done? In our chapter, we focus on learning infrastructure, not physical infrastructure. We suggest that educators develop a “pedagogy of adaptability,” and participate in building “flexible, resilient systems of learning for an uncertain future.”

One of the tenets of such a system is to foster independence in students; give them control over their learning to the extent possible. We want to empower them to continue learning with less guidance during an interruption. Part of doing that is making sure the things they are learning feel useful and meaningful to them. This could include teaching them the building blocks of resilience itself—disaster response, even survival techniques. What’s probably more important than the specific curriculum is an element of learner choice.

A complementary idea is to build relationships of warmth and trust as much as possible among a school community. These can become buffers, sources of additional support when life goes topsy-turvy.

Technology can certainly help with all of this, although it’s a tool, not a solution.

It should be obvious, but these insights don’t just apply to education. Think about your field, if it’s activism, a small business, any kind of service provider. Where is your adaptability? Who can you empower further? What relationships can you strengthen? What will you do when the chips become the cookie?

Some Links

We Are The Great Turning, the podcast I produced featuring the 95 year old climate and spiritual leader Joanna Macy and Jess Serrante, is featured as a selection for Tink Media’s Audio Delicacies 2024! This is a long, rich and wonderful list of the best podcasts/episodes of the year.

Thanks for this post! Your framework of "interruptions becoming ongoing conditions" really resonates with my teaching experience. Since Trump 1.0, the pandemic, and the protests, I've shifted toward more lightweight, adaptable frameworks and specifications based grading models rather than rigid rubrics. The challenge I keep running into, though, is how institutional infrastructure doesn't always support this flexibility. Just this past term, I served on a committee advocating for basic teaching tools like the ability to project onto screens and not be placed in rooms without windows and bolted down desks.

The other elements you discuss like childhood trauma and toxic screen use are just rampant in my students. Trauma informed approaches became clearer sticking points in my graduate course on empowerment pedagogy. But we can only do so much when university counseling and psychological services run sometimes months out for students to be seen.

While I've become nimble in my teaching approach, I’m not sure how much these students can realistically take without losing all steam. AI makes many question why they need to study or go to school at all. Meanwhile, I often feel like the institution maintains tight control over endowments and our actual capacity to adapt. Thank you this piece! I’m so grateful to have found your work this year.

Hi Anya, as a teacher in Australia who taught through the pandemic lockdowns and home-schooling my own daughters at the same time, this is such an important post. The notion of learning through emergencies, and the normalisation of crises as the way classrooms must now operate is very accurate in my experience. I really like that you're able to take a positive and forward-thinking position in this new form of education. It definitely motivates me as an educator to strive toward adaptability as a trait of strength rather than a survival tactic. Thanks very much.