Hello friends.

This is my regular Friday weekly essay. It will always be freeee! Paywalled posts now on Mondays, free posts on Fridays.

I started this essay in the fall, after Hurricane Helene. Remember that one?

The mountains of Western North Carolina—inland, abundant water, temperate—were once touted as a “climate haven.” I have friends of friends who relocated there from New Orleans after Katrina because they were tired of dealing with storms.

In fact, in 2023 Asheville was named third on a national list of resilient cities likely to see an influx of climate migrants. They were worried, back then, about overcrowding, and “climate gentrification.”

Now, some families there are going to be living in hotels till May 2026.

I spent the week of January 20 in New Orleans, my hometown. One of the friends who joined me came from Los Angeles, where her family had a go-bag packed and was watching the wind the previous week.

When she said she was from LA, locals gave her the most sincere condolences. They get it. They really really get it.

Naturally, our conversations that week turned more than once to this question: do you stay or do you go? What’s a safe place? Is there a safe place? The Great Lakes? Costa Rica? Norway?

As climate change accelerates, as the searchlight of destruction sweeps from east to west and north to south, it will leave these questions in its path again and again: Where do we go? How do we get away from this threat? Should we rebuild?

And this same anxious dialogue pertains to the United States as a whole now. Our political system looks to be crumbling before our eyes. Do you pack your bags, get a European passport, aim for higher ground? Or do you keep your head down, try to protect the vulnerable, and prepare to rebuild when (if) it all passes?

This question makes me itchy for a lot of reasons.

First of all, this year will mark 20 since Katrina.

I feel lucky being from Louisiana for so many reasons. A dark one is that we went through our first big climate trauma early, back when these events were spaced out a bit, before the national spotlight moved on so quickly. We had some time to process, you might say. The experience of being in the city in the immediate aftermath of the storm, as a reporter, a volunteer, and a daughter, set me on the path I’m on today.

Back then many people were quick to write off this beloved, beautiful city, in the name of safety. Big plans were drawn up to turn neighborhoods into parkland. But New Orleans is still here.

Not to say it’s fine. It is as fine as the coffee-drinking dog in the meme.

Besides the recurring nightmare of storm season, which could take them out any year, any time from June through November, my parents are dealing with street flooding, boil-water advisories and transient power outages so regularly that they barely bother to bring it up. There’s been a few random building collapses. A Mississippi river drought threatening the water supply. Racism and poverty, violence and corruption, Airbnb and gentrification. That terrorist attack—remember that? A whole long month ago.

The Lower Ninth Ward still has big blank spots. And a whole lot of people weren’t ever able to make it back. In particular, the city’s Black population has dropped and keeps dropping.

But on the other side of the ledger is the fierce love people have for this would-be sacrifice zone. The exuberance of participatory culture, the sheer time dedicated to creativity and celebration, civic engagement and community connection, kindness and beauty—all of it is unmeasurable and off the charts. Nobody takes living here for granted—as they shouldn’t.

When an unprecedented snowstorm shut down the city, you could see that people had their priorities straight. The supermarket the night before had long lines, but everyone was calm and polite. They knew the drill. With 9 inches on the ground and still falling, an old friend invited me out for a drink in the Bywater. At 4pm the bar was packed with a mix of stranded travelers and jubilant locals drinking hot toddies from paper cups. The manager had planned on staying closed that day, but changed his mind “because he thought it would be fun.” People at the airport were kind, considerate, and joking around, even after two straight days of canceled flights.

runs “personal ruggedization” courses designed, among other things, to get people thinking about where they might live given all that’s happening. As he wrote on X:

…There are no "climate havens." Some places are *relatively* safe. Indeed, the risk gap between the most endangered and the best-sited places is pretty huge.

But everywhere you might go, you'll have to be ready for some mayhem.

He helps people think through the dynamics of places people are leaving and places they’re going. The places perceived as safer might see “boomtown dynamics and opportunity hoarding,” he says.

Whereas the places that are abandoned by those with means might enter a kind of climate doom loop.

People will get trapped in these declining brittle places. The combination of precarity, concentrated poverty, dwindling responses and despair (with all the violence, addiction and abuse that brings) will make it hard for a lot of people to leave no matter how bad it gets.

All of these phrases apply to New Orleans, yet none of them capture what it feels like to be there. The wealth of this city is in its community, and it’s abundant. That’s another valid reason it’s so hard to leave.

I’m not gong to argue against the risk gap Steffen is talking about. You couldn’t pay me enough to move my family to Phoenix or even Breezy Point.

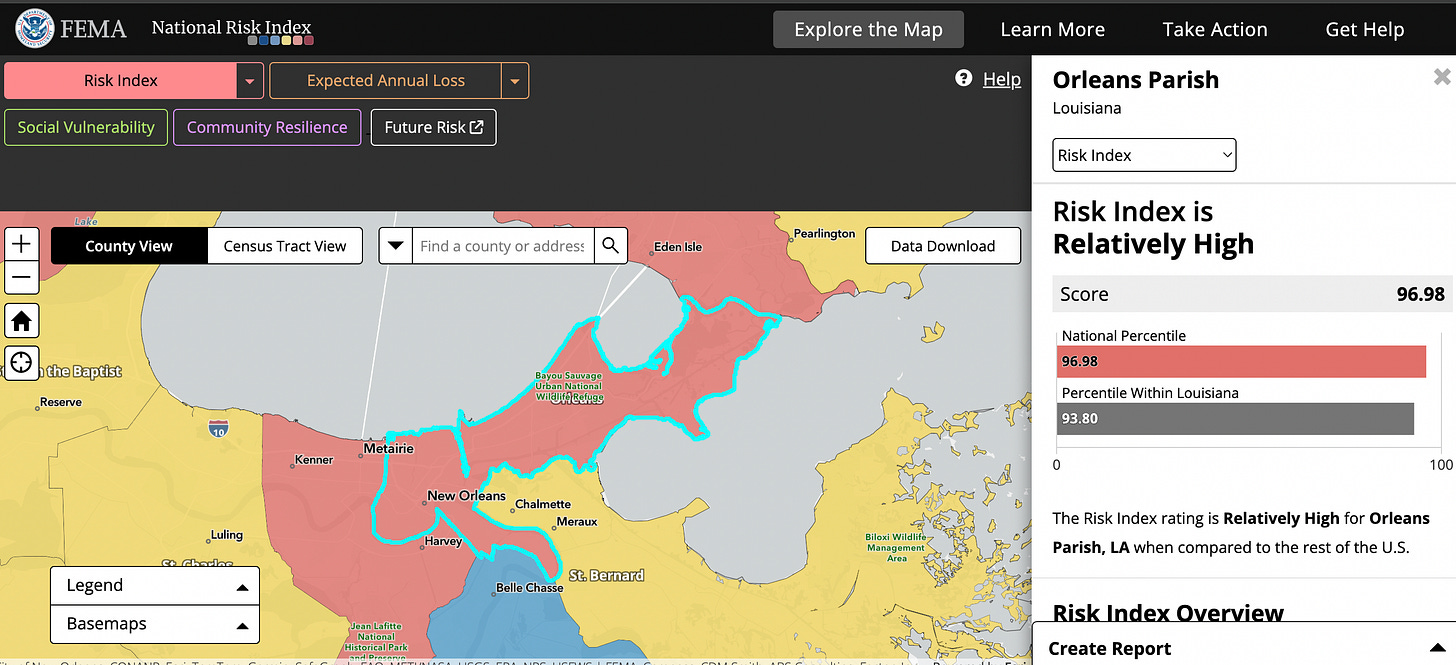

(Look up your home on the FEMA risk map).

Then again, if I knew those places, and loved the people there, I can understand looking for reasons to stick around and make the best of it.

So for me, the first answer to the question “Where should you move to be safe,” is “No place is surely safe.”

The second response is a battery of questions.

Do you truly understand the risk profile of the place where you’re living now? What’s the quality of your support system? Where are you in your life span, and what are your priorities? What is your capacity to rebuild, to start over, or to absorb the shock of destruction? How are your survival skills? Do you know how to function without electricity or clean water from the tap? Do you give more than you get from the community you’re in? Do you expect that to change?

If you lost everything you own, what would you miss the most? Would you rather put on a respirator and sift through ashes, or put on a respirator and sift through moldy, waterlogged piles of your possessions? Would you rather track a hurricane’s spaghetti plot, or monitor the direction of the winds and the dryness of the brush?

By nature, do you prefer to run, hide, or fight?

As climate change advances, I fully anticipate homeownership becoming less common. I imagine more people adopting semi-nomadic or seasonal migration, maybe intentionally building up social capital in more places. Online networks allow us to maintain friends and relations and support each other from near and far. That becomes a clutch move as the eye of tragedy keeps roving.

Elizabeth Sawin directs a thinktank dedicated to “multisolving” interconnected problems. Using systems thinking, she’s working on applications that address climate change, health, equity, biodiversity, and economic vitality all at once. She posted on LinkedIn:

I don't think climate "safe havens," if they exist, are places. I think they are a direction not a guarantee and I think they look like movements towards changed thinking, towards design for a destabilizing climate, towards...

...commitment to wellbeing of one another, and most of all towards changes in power and its uses to enable the changed thinking, design, investment, etc.

I agree. And I responded, “I think safe havens are found in webs of relationships with each other and with the land, stored-up knowledge of practicalities and subtleties that we accumulate and share.”

And sometimes in a song. Or just one moment of solace.

Thank you for this post. It's truly insightful to get this perspective from another American. Our family has been considering a move overseas long before anything really concerning began happening in the US. Now we are feeling it strongly, but it is more politically motivated than anything else. We live in the deep South - need I say more? It is hard to build resilience and community in an area so focused on closing their eyes and ears to the collapse that's happening all around.

The questions are ones I’ve been asking myself for over a decade now, during which 2 bushfires, 3 floods and a cyclone ravaged my region in Australia. We are known for our rugged-ness but it still eats away any attempt to stay positive for future generations. I like how Meg Wheatley describes the need to create islands of sanity to create a resilient, safe and caring place in preparation for what’s to come.