Overcoming Denial

How to cure blindsight when it comes to sexual predators, climate change and atrocity--and in our everyday life

Three years ago I had a jarring experience. The beloved teacher and mentor of several of my best friends in high school was exposed as a serial predator and rapist.

I met Mr. Bailey (as we all called him) at the age of 15, when my family moved to New Orleans from Baton Rouge. I didn’t understand why my new friends were so enamored with their former middle school English teacher, or why he hung around with them, either, but his presence seemed sanctioned by their parents. I found him smart, eager, funny, and handsome in a preppy way, with floppy hair and glasses. He asked me to coffee a few times, just the two of us. He recommended books to me. We stayed in occasional touch as he left teaching and became a massively acclaimed literary biographer—I reached out and asked him for advice as recently as 2020.

Mr. Bailey turned out to have been, all along, exactly what I initially suspected him of being. That was only part of what floored me. The really wild thing was that when I started calling my classmates and comparing notes, a couple of them remembered something I had 100% blocked out— that the night we first met, while we were sitting on the couch at a party, he took out a pen and started drawing all over my arm. My inner forearm, up to the elbow.

As soon as they mentioned it, the memory suddenly clicked back into focus, and chills ran through me. There’s no world where that’s a normal thing for a grown man to do to a 15-year-old he just met, right? I surely knew that, on some level, even back then. But everyone around me was acting like it was totally chill--more than that, that I was lucky to get the attention. These were my new friends, and I wanted to fit in. So I let it go, and eventually—proof positive that I knew it wasn’t okay—I buried it completely.

I was terrified that my own mind could do that. What else might I have repressed?

The mechanisms of denial have been on my mind recently. I’ve been thinking about the bloodthirsty things that Donald Trump says on the campaign stump, and how the mainstream media seems determined to “sanewash” him, and his supporters just don’t believe him. “In the latest New York Times/Siena College poll, 41 percent of likely voters agreed with the assessment that “people who are offended by Donald Trump take his words too seriously.”

I’ve been thinking about the torrents of hurricane-related conspiracy theories that seemed to motivate at least one North Carolina man to threaten FEMA workers with a gun. In the face of increasingly chaotic weather, climate denial is morphing into a desperate search for someone to blame, as Mary Annaise Heglar writes:

It is human nature to try to find meaning in the world around us. As the world gets crazier and more unpredictable, the more prone we are to make up wilder, more fantastical stories. But once a conspiracy theory has a bogeyman, that means it has a target and that’s when things can get dangerous….

As Heglar also points out, it’s easy to laugh at and feel superior to people who purport that hurricanes are caused by space lasers.

That’s until you realize the more sophisticated flavor of climate denial you and I may be engaging in.

A recent commentary by Wim Carton and Andreas Malm lays things out this way.

The Paris Climate Agreement in 2015 set a threshold of 1.5°C of average warming above pre-industrial levels. Scientists had determined this to be a more or less “safe” level. But achieving it would require very fast, very deep cuts to fossil fuel use. That would be expensive. Especially for fossil fuel companies.

So scientists started producing what were called “overshoot” models. In these projections, we first go over 1.5 degrees, and then we come back down, via some nascent or not-yet-developed technology for pulling carbon out of the atmosphere. This image comes from the Washington Post, and shows a number of different paths—some where we stay far above that safe limit for decades. Note that the graph calls these paths “hopeful”.

Unfortunately, as a new paper in Nature points out, crossing 1.5°C even temporarily risks irreversible damage—tipping points, some of which produce feedback effects. These include sea level rise, permafrost thaw, and extinctions. Also, it bears repeating that “current removal rates from [carbon dioxide removal] methods other than afforestation and reforestation are minuscule.”

So basically the entire “overshoot” conversation is more or less a fantasy—an elaborate, scientific-sounding form of denial that almost all serious climate policy folks nonetheless engage in.

Climate scientists do not really think we’re going to keep warming to a “safe” level. In a 2024 survey by the Guardian, 77% of those who know this topic the best, believe the world is destined to heat to 2.5°C or higher. But we’re still carrying on international discussions about the 1.5°C target, and failing to reckon, loudly and publicly, with the real implications of 2.5°C and up. This is textbook denial.

A third form of denial I’m thinking about has to do with the ongoing actions of the Israeli army in Gaza. The New York Times published a piece containing the testimony of 65 medical volunteers who have been in hospitals there. 44 of 65 said they had seen multiple small children shot in the head or the heart.

This is in the Sunday paper, weekend of Yom Kippur, in big print. I turned it over on my breakfast table, because I didn’t want to talk to my 7 year old about the child who had his jaw shot off and was slowly choking to death on his own blood while fully conscious.

63 of 65 medical workers said they saw Palestinians starving. U.S. law prohibits military assistance to countries that impede humanitarian aid. Continuing to arm Israel months after the United States tried to build a pier to get food into Gaza from the ocean because the army was not letting trucks through, and after the army has killed more than 300 aid workers, and while independent sources say there is a famine, requires denial on the part of our elected officials. (The Secretaries of State and Defense this week sent the Israeli government a strongly worded letter making this point, which seems to have yielded some results.)

The killing of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, confirmed yesterday, may put a ceasefire within closer reach; but if history is any guide, the real reckoning can begin only after the bombs stop.

States of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering is a 2001 book by the sociologist Stanley Cohen, whose political consciousness was first awakened as a Jewish child in apartheid South Africa. He lived for many years in Israel, intimately witnessing the widespread denial there of the treatment of Palestinians.

The book is an anatomy of the denial we engage in as perpetrators, bystanders, even as victims of harm, at the level of family, community, and nation.

Outright denial-it didn’t happen/it’s not happening—is only the beginning.

There’s also:

discrediting-the source is biased/manipulated/gullible

renaming-yes, something is happening but not rape, not genocide, not fascism. Let’s argue over semantics

justification-it’s happening but it’s justified

denial of responsibility—it’s happening but it’s unavoidable. There’s nothing to be done about it. Certainly not by me.

interpretive denial —it’s happening but it’s not important. Or it doesn’t mean what you say it means.

implicative denial—it’s happening but we ignore the implications. We don’t respond, we brush it off, we joke about it— aka minimizing.

My friend

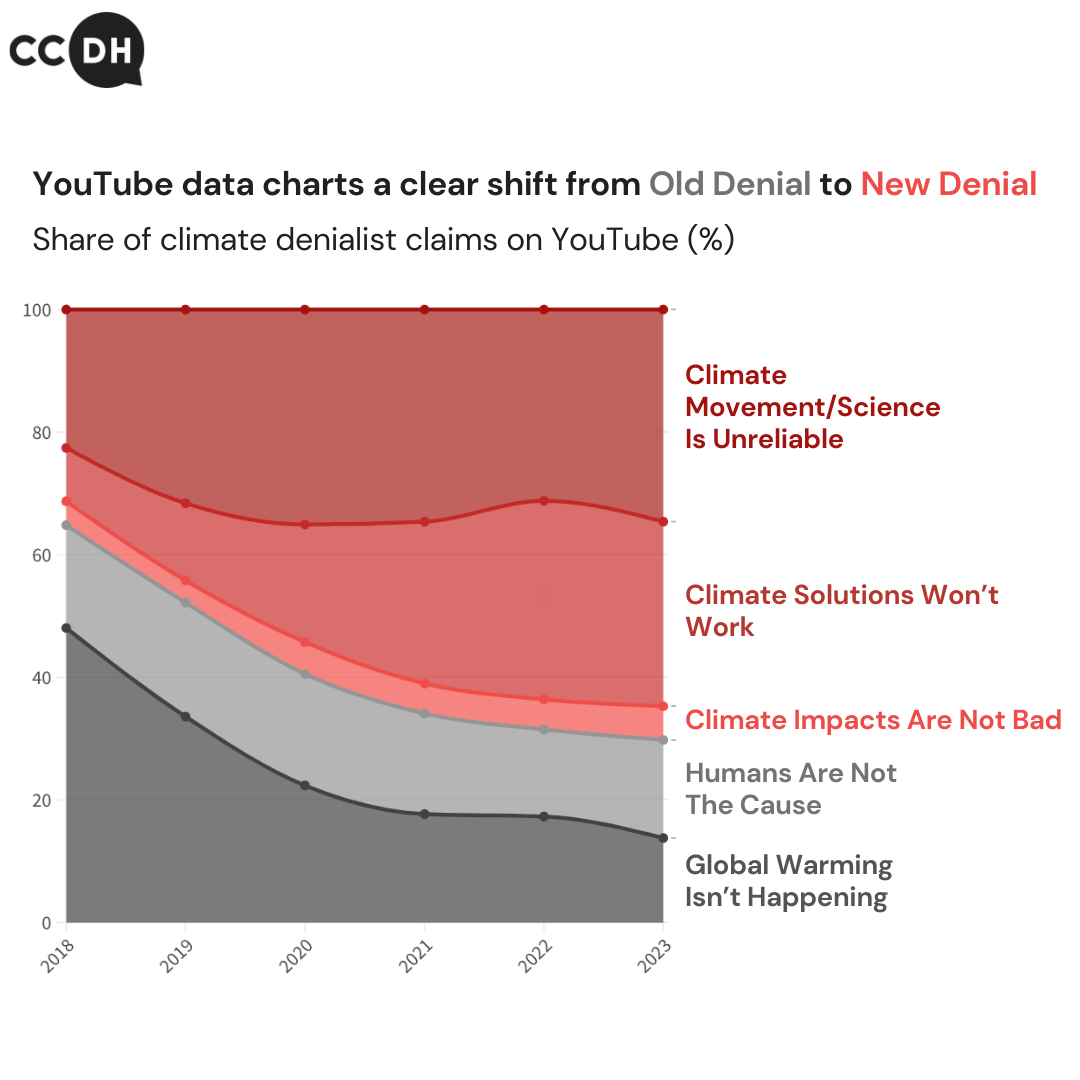

wrote in a recent issue of his great Substack that climate denialists’ claims on YouTube have mutated—from “climate change isn’t happening” (outright denial) toward “climate movement/science is unreliable” (discrediting) and “climate solutions won’t work” (denial of responsibility). Image from Center for Countering Digital Hate.Implicative denial may be most chilling, because it’s most banal. It’s when bystanders, well, stand by—denial by looking the other way.

As we experience compassion fatigue, and our emotional circuits are overloaded by the contemplation of suffering nearby and far away, “worse than torture not being in the news,” Cohen writes, “it was no longer news.”

We enact “Not the crude lying of cynical apologists, but the complex bad faith of those trying to look innocent by not noticing.”

Or what sociologist Kari Marie Norgaard calls, in the context of climate denial among the privileged, the social “construction of innocence.”

According to Cohen, the opposite of denial is acknowledgment. As a society, we can engage in a “transition to justice” through processes of truth and reconciliation.

Trials and public testimony. Naming and shaming, kicking the bums out. Memorial sites and memorial days, official apologies, reparations and restitution.

Overcoming denial ultimately requires doing something about the problem you’ve been denying, and that may be the hardest part. But we have no real choice.

As the Gospel of Thomas has it: “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” Or as James Baldwin put it:

Denial can start small. Sometimes it feels necessary. And as a woman, it is conditioned in me. Compartmentalization, repression of true feelings, swallowing hard and smiling at things that aren’t funny, looking past some unpleasant realities to keep the peace.

Denial is a central feature of addiction and eating disorders. It’s also very, very common with sex offenders. Not only do the addict and the predator deny outright, discredit those who point out the truth, rename and justify their actions, shirk responsibility and avoid the implications—so do their enablers, and even their victims.

As an antidote, steps 4 and 5 of the 12 steps, in AA, prescribe a sort of personal truth and reconciliation:

“We: made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves;

admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.”

But how do you get started? Confronting people with the stark truth won’t necessarily work. Denial deflects the truth beautifully. That’s what it’s designed to do.

Maybe we need to think instead about how to clear a little room for people to be honest.

Denial arises when people feel helpless, hopeless, and complicit. They fear the negative consequences of the truth. They don’t feel equipped to make a positive difference in the outcome. They don’t want to be the bad person who did those bad things, or let those bad things happen. Be it climate change or war, the bad thing that is happening, Norgaard writes, challenges our safety and our innocence.

It follows that overcoming denial might involve giving people something to hope for, making them feel less alone, and perhaps, blunting the shame of failure. That we might want to replace the search for safety, with a sense of bravery; the desire to preserve innocence, with a confidence in the process of redemption and repair. A granting of amnesty, perhaps, not for the harm that’s been done necessarily, but for the time that you spent looking the other way, feeling that you couldn’t do enough and therefore doing nothing.

A small study of group alcohol treatment emphasized the importance of feeling accepted by others in the group, which helped people further accept themselves, which paradoxically, can lead to change. “Catharsis, hope, and identification were also associated with decreases in denial and psychopathology.”

Overcoming denial requires giving up your cherished innocence. I am sorry that as a teenager, a newcomer not quite under his spell, that I didn’t follow my instincts about Mr. Bailey and say something. Many girls could have been saved from harm if he’d been called out earlier.

Although it’s much more comfortable to look the other way, I tried to right this wrong in part by asking my 8th grader recently about creepy teachers. They have already come across a few. I let them know that 1) the rumors are often true, 2) anything they share, they will be believed.

A friend and collaborator of Stanley Cohen wrote his obituary, in The Guardian, in 2013. He said the great man himself wasn’t immune to the charms of denial, even in the form of a joke:

I had, I told him, recently read a comment by the actor Richard Burton, who had given up all alcohol; it was a wonderful thing, he said; now at last he could see the world as it really was. Stan waited for my little sermon to end before looking up and saying: "That's all very well, but who the hell wants to see the world as it really is?"

Links

Important new research on youth mental health and climate. Climate Mental Health Network has details.

Global emissions may have peaked this year! This is huge, even though it’s insufficient.

Appreciate this very much, especially the types of denials that people bring to this (and other) conversations.

I'm wondering if you've read "Hospicing Modernity"? In it, Vanessa Andreotti talks about our "Four Denials" that we must grapple with before we can move forward with relevance:

--the denial of systemic violence and complicity in harm (the fact that our comforts, securities and enjoyments are subsidized by expropriation and exploitation somewhere else),

--the denial of the limits of the planet (the fact that the planet cannot sustain exponential growth and consumption),

--the denial of entanglement (our insistence in seeing ourselves as separate from each other and the land, rather than “entangled” within a living wider metabolism that is bio-intelligent),

--the denial of the depth and magnitude of the problems that we face: the tendencies 1) to search for ”hope” in simplistic solutions that make us feel and look good; 2) to turn away from difficult and painful work (e.g. to focus on a “better future” as a way to escape a reality that is perceived as unbearable).

This chart is also helpful in understanding the layers. https://decolonialfutures.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/four-denials-four-layers-1.pdf

Hope this adds to the discussion.